This is the second in my “Reflections” series where I am sharing stories from my family. I am a Mexican-American Puerto Rican woman living in Arizona.

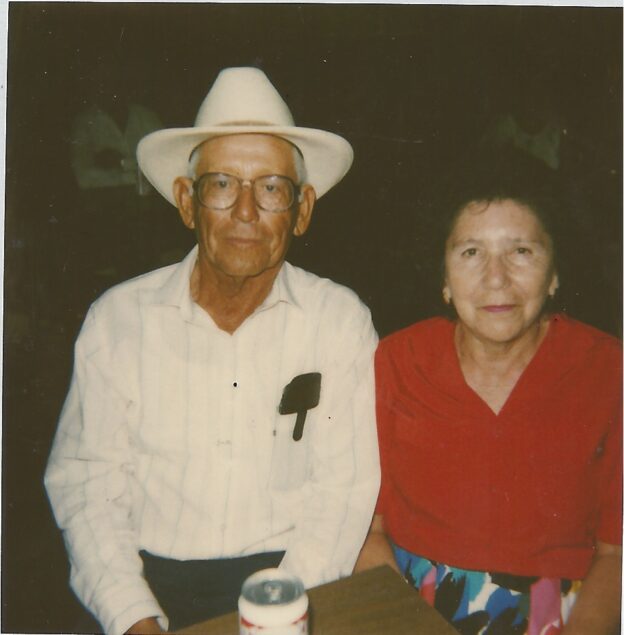

I wrote about my Mexican-American grandfather only receiving a second-grade education in my first post about my family’s experience. In that post, I mentioned that I didn’t know how long my Mexican grandmother had gone to school. I asked…it’s taken me a week to process her answer and write about it.

First – just a little more about US history. This is a very basic overview since I want to write a little more about my grandfather’s history before I write about my grandmother, and then circle back around to our place as Latinos in the school system. And really then, the place where all stories seem to end and begin: love.

So…Texas. My perception of Texas is derived from Texans…both my mom’s family and my husband’s family have Texas roots, and by all accounts it is, THE GREAT STATE OF TEXAS. Did you know that there are actually six United States in the continuous states to have been sovereign before they joined the Union? There is something missing from that last list…Do you know of another state was a recognized sovereign country? HERE is the answer.

So, Texas was once the Great Republic of Texas. Do you know where the land grant came from? If you guessed Mexico, you are correct. So, to continue the history of land appropriation…the Spanish took it from the Native Americans, and a group of invested US citizens took it from Mexico, established their own country, fought some battles, and declared themselves to be the ruling party. This is obviously over-simplified…HERE is a good place to go for the actual details. As you click on the sub-topics, more details get added to the timeline…not a surprise that it starts with Anglo perspective and adds in as you click…(sigh). At least they tell more of the story than you ever learned in school.

So my grandfather, who only got a second grade education, was a product of a segregated school system. There wasn’t even a pretense of “separate but equal”. The Mexican communities that were aggregated into the state were deemed inferior and unworthy of education. According to my grandfather, the schoolteacher sent to educate the Mexican children where he lived spent more time in the car with her boyfriend than she did teaching school. The state did not send a teacher back to his school after his completed second grade, so he started working the family business: agriculture.

I am unclear as to whether his younger siblings got an education. Teachers for the Mexican community may have been funded again after my grandfather started working. I will have to ask his remaining living brother who lives in Arizona to see what he remembers.

So back to my grandmother. When I asked her how long she went to school in Mexico, she answered, “Fifth grade”.

When I asked her why she stopped going to school, her answer floored me. Here it is, loosely translated. From now on, I am only asking her questions like this with a voice recorder so I can share her Spanish answer as well as the English translation:

No one told me to go to school. I was born after my mom turned forty. She was embarrassed to be so old and pregnant, and she didn’t love me. When my sister died in childbirth, she ignored me and didn’t bother with me ever again. I can’t remember who took me to school when I started. After fifth grade, I didn’t want to go back and no one made me, so that’s where schooling ended.

Even as I write it out today, seven days later, I am still moved to tears. I had our youngest child at 38. I would never even conceive of being embarrassed – I was so grateful to be pregnant again considering I was told I would never have children.

I cannot imagine how it is to grow as an unloved child. She had told me before that her mother was an absent mother, and that she had other children that she was more involved with, but I had never heard her say so clearly, “Mi mama no me quería”, which actually is deeper than not loved, it means, “not wanted”.

I chalk up her candid retelling to the loss of filter that I see happen when people age. It’s as if the elderly need people to hear their truth, instead of the more sugar-coated and comfortable re-written version they have been presenting to the world.

So I sat with that. I have friends and acquaintances who care for foster children. I have heard their stories and seen some of the trauma their children live with. The trauma of abandonment and being unloved is real. It is complicated, and it is deep. Then I sit with it and feel into it as a thread that weaves into our family. I know it is unfinished story, because I have heard the term spoken by some of my elders, and they have called themselves, “the black sheep”. The one that is outside, different, unseen, unloved.

Like all tapestries, there is more than one thread. So unloved and abandoned is one of them that weaves into the color of our blanket. Another one that has been woven into the fabric is education.

In spite of of their own shortcomings as parents and lovers, both of my grandparents decided early on in their relationship that their efforts were going to be turned to providing food and shelter for their family above all other wants, and ensuring that all of their children completed high school. For their time, it was rare for seven girls to stay in school past the age of 16 instead of getting jobs to help support the family.

Yet they held fast to their goal in spite of the comments from the extended family that the girls were being wasted by continuing to go to school. Of course, no one questioned that the son should finish high school. Of course he should go on and exceed the life of the parents. But the girls – blech. They were expected to be domestics, seamstresses, waitresses, cooks – whatever it was that was available to girls who quit schooling at 16 to help support the family.

My mom and my aunts suffered in school. They were made fun of because they wore home-made clothing. They were ridiculed because their lunch was made with beans and a tortilla instead of white bread (saving commentary on this for a future post on appropriation). The first set of sisters to go through school was teased about their accent because all of them were ESL students even though they had been born and raised in the United States. I need to ask when the older siblings started teaching the younger siblings English, because I don’t remember that all of them started as ESL students.

But they endured. I am so proud of them all for persisting through this otherness. All of them completed high school. And several went on to pursue college and beyond that, advanced degrees in administration and law.

And even though they weren’t perfect parents, and even though both of my grandparents have stories of being wronged by their family and feelings of being unloved, although indications are that the trauma persists… thank God they agreed that they would be a united front in insisting that their children had to be educated. In that education were sowed the seeds of possibility. All of them did more and became more than was typical for their time.

My mom graduated high school in 1967. I would hope that fifty years later, it wouldn’t be a big deal to see brown people in school. I wish that it wasn’t a reason for reaction when people to see us in school. I wish people weren’t still surprised that we could succeed in school.

I heard, and still hear the question, “How long have your people been in the country?” or when people hear me speak Spanish, “Where were you born?” As if my value as a human is going to be determined by the longevity of my ancestry (hmm – longer than yours, most likely invaders nonetheless) or my place of birth (California).

So how do we heal from the years of pitching people against each other as inferior or superior? How do we find a way forward from the hurt we inflict on each other?

I used to think that being colorblind was the goal. Our children have taught me that is wishful thinking. Children see everything, they notice everything, and they call me on my attempts to ignore the obvious. If I tell them, “A person isn’t ___, they’re human,” they are going to state the obvious, “Yes they are ___…they (obviously) look different than me”.

What might we strive for then, if it’s not colorblindness? I go back to an ancient word, “Namaste”. One of the ways it’s translated is: “The divine light in me sees and honors the divine light in you.”

What if we took that to heart? We are all “fearfully and wonderfully made”, to pull from another ancient text. If we believe that all of us are divine, intentioned to be here, then can we have more compassion? Can we wait and look someone in the eye, see them as another person, equally in their right to be in space with us, and then talk to them with a heart of love instead of speaking with fear?

I don’t know. I hope so. Lead with your heart and your light today. I would love to hear about how it goes. Maybe we can be the start of a new legacy: the world that rose from fire and lived with love.